In May 2020, the annual conference of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC) was meant to happen in Montreal. The team behind the Centennial of Broadcasting in Canada had arranged with the staff at McGill University's Marvin Duchow Music Library, also involved with the planning of the ARSC conference, to create an exhibition for conference participants. Even though the conference was eventually cancelled, in this page we offer the content that was meant to be displayed at the Music Library.

The end of the First World War saw a return to civilian testing. Going forward, in addition to amateur radio operators, there were many others who had learned about wireless telegraphy during the war. Some obtained their amateur radio licence and could therefore receive wireless telegraph messages from different areas across the globe. Companies began creating stations that could transmit in amplitude modulation (AM).

The world of wireless telegraphy transformed itself to make room for the wireless telephone, allowing two individuals, separated by geography, to communicate by voice. It was soon realized that the radio telephone not only allowed communication between two distant stations, but also that the instrument made it possible to reach thousands of people simultaneously. There was a rapid transition from radiotelephony to broadcasting.

In Montreal, the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of Canada obtained a licence for experimental broadcasting and using the call letters XWA, went on the air in December 1919 from a studio on William Street.

In May 1920, it produced a radio program that featured some songs and speeches for Canadian scientists attending a Royal Society of Canada conference in Ottawa.

Thereafter, radio programming became more frequent and better structured. In November 1920, less than a year after the debut of stationXWA, it was announced that the “Berliner Concert” would be broadcast. Another concert was also scheduled to be aired on December 31, 1920, which made it look like 1921 was going to be “the year of radio.”

In 1922, the Government of Canada authorized the first operating licences for commercial radio stations. Some 21 permits were issued, beginning in April of that year. By December, there were 37 more. In Quebec, they included following stations: CKAC (La Presse), CFCF (Marconi), CJBC (Dupuis Frères), CHYC (Northern Electric), CFZC (Canadian Westinghouse), CHCK (L.B. Silver), CKCS (Bell Telephone), CFUC (University of Montreal), CFCJ (L’Événement in Quebec City)(1).

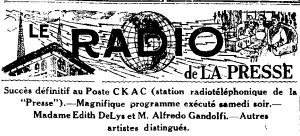

In May 1922, the daily newspaper La Presse announced that station CKAC would commence broadcasting in the fall. The person responsible for this innovation was Jacques-Narcisse Cartier. Originally from Saint-Hyacinthe, Cartier first trained as a radio operator at the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company in Nova Scotia. CKAC and CFCF, which replaced XWA, shared the same frequency for a number of years — something that was not uncommon at the time. The shared frequency resulted in both English and French programming being aired alternately at different times of day.

Station CKAC proceeded with tests in September 1922 and the first official broadcast aired at the end of the month on Saturday September 30. La Presse reported the following:

Source: BANQ 3762248 CP023594

“The Saturday evening program lasted, without interruption, from 7:00 to 11:30 p.m., courtesy of the Marconi company (station CFCF, in the Canada Cement Building) which took a break in their programming between 8:00 and 9:00 p.m. to allow station CKAC to air a continuous broadcast(2).”

Radio broadcasting emerged at the speed of lightning. From the initial 20 or so starting in the spring of 1922, the number of commercial radio stations increased to more than 80 across Canada by 1928. The number of reception permits jumped from 1,200 to 760,000 between 1921 and 1931! The Canadian National Railway Company (CN) formed the first Canada-wide network of stations during this decade. It was partly because of this first network of radio stations that the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), which included Montreal stations CBF and CBM, was established in 1936.

––––––––––––––––

1. Pierre Pagé, L'histoire de la radio au Québec, Fides, 2006, p. 447.

2. La Presse, 2 octobre 1922, p. 17.

During the 1920s, few disc recordings were made and the majority of them had been recorded mechanically, which resulted in poor acoustic quality. Since its inception, the CKAC studio was designed as a small concert hall, which made it possible to bring in musicians and broadcast live music. During the station’s inaugural concert, some 15 artists took turns at the microphone. And, on January 27, 1923, La Presse announced to its readers that its studio now had a Casavant pipe organ(1).

The Marconi station, CFCF, was not to be outdone. In June 1922, it organized a Radio Week:

“Tomorrow evening and every evening next week, at 8:30, we will offer a special radio concert at our six theatres in addition to our regular programming. Think about it! Singers, instrumentalists, and brass bands, from miles away, will cheer you up(2)."

From February 1923, CKAC began a series of programs aimed at introducing music and songs from France to Montrealers. The series was under the direction of Raoul Vennat, a French-born music importer. Artists of the time, like soprano Anne-Marie Asselin or bass Armand Gonthier, performed contemporary compositions. In June 1923, CKAC broadcast its first operetta entitled Les Cloches de Corneville. The broadcast was a large- scale production in which the dozen soloists were surrounded by a 30-person choir and an orchestra with 25 musicians!

In 1929, the station negotiated an agreement with the American network CBS. The agreement allowed CKAC to locally broadcast classical music concerts produced in large American cities, and even some in Europe. In return, the CKAC symphony orchestra, directed by Edmond Trudel, would be broadcast several times a week on the American network(3).

Thus, music and opera have been on the radio since the very beginning.

––––––––––––––––

1. La Presse, 27 janvier 1923, p.15.

2. La Presse, 17 juin 1922.

3. Pagé, op.cit., p. 322.

From the onset of the radio, stations had broadcast programs geared toward the middle and upper classes, given the high cost of receiving apparatuses. The stations, therefore, had typically broadcast classical music and opera for its new listeners. But as the price of radios decreased, the number of listeners grew in all socio-economic classes. In addition, in 1925 the quality of disc recordings improved as processes evolved. While discs were bought only by those who had a gramophone — and later a record player — at home, playing those same discs on the radio reached a larger and more distant audience.

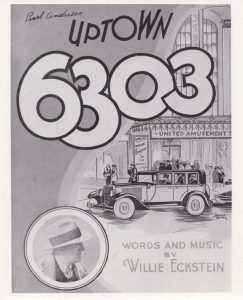

New artists appeared on the radio. One of the first was likely Willie Eckstein. Originally from Pointe- Saint-Charles, the ragtime musician and silent movie pianist would have been invited to play at the newly established station XWA.

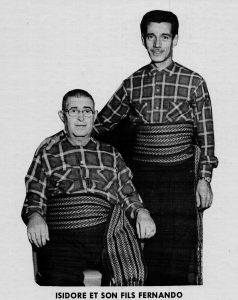

In 1924, folklorist Conrad Gauthier performed on a radio program for the first time at Montreal station CKAC. Fiddler Isidore Soucy was on the air between 1926 and 1930 as part of the program Living Room Furniture at CKAC(1). Other voices, like those of J. Hervey Germain, Jacques Aubert and Mary Travers, better known as La Bolduc, also performed on radio. In the 1940s, the young Marcel Martel sang on radio stations CHLN in Trois-Rivières and CHEF in Granby(2).

In the 1940s, Alys Robi became more and more popular among Montrealers with her Latin American repertoire. She performed live regularly at CKAC, and made some 78 rpm recordings(3).

More efficient microphones allowed a new texture of sound to spread. Crooners, adept with the microphone, developed their own new sound. Lionel Parent and Jean Lalonde were among these new Quebec performers.

Also, several radio programs helped launch many careers. Guy Mauffette hosted Baptiste et Marianne in the 1950s, which provided Felix Leclerc an opportunity to perform. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the singer and composer Fernand Robidoux hosted several programs in Trois-Rivières, Sherbrooke and Montreal, during which he introduced young Quebec singers, like Raymond Levesque(4).

One of the few English Canadian artists on the radio was Montreal native Alan Mills who hosted a CBC radio show called Folk Songs for Young Folk from 1947 to 1959. The show promoted both English and French folk music. Unfortunately, most private English language radio stations were completely indifferent to Canadian singers, songwriters and bands until the formation of the Canadian Radio-Television Commission (CRTC) in 1968, which forced radio stations to include Canadian content in their programming.

––––––––––––––––

1. Jean Du Berger, Jacques Mathieu et Martine Roberge, La radio à Québec, 1920-1960, PUL, 1997, p. 145.

2. Retrieved from [http://lequebecunehistoiredefamille.com/stars/marcel-martel].

3. Retrieved from [http://www.qim.com/artistes/biographie.asp?artistid=231].

4. Jean-Nicolas De Surmont, « L’impact de la radiophonie commerciale sur la poésie vocale québécoise », Revue internationale d’études canadiennes, nos 39-40, 2009, p. 75; Retrieved from [https://doi.org/10.7202/040823ar]

Throughout the 1920s, radio stations were only broadcasting a couple hours a week. Gradually, air time increased, and stations began diversifying their programs. A few news bulletins were introduced (in the evening as to not interfere with the sale of morning newspapers), as well as stock market numbers and sketches and plays. On April 5, 1923, CKAC broadcast a play by Louis Frechette entitled Félix Poutré, and then another La malédiction, in June of that same year.

In 1929, the program L’Heure Provinciale was aired on CKAC. This educational feature, under the direction of Edouard Montpetit, was subsidized by the Quebec government. Each week, the program offered a number of speakers, as well as musicians, composers and Quebec writers. Musician and playwright Henri Letondal and actress Juliette Beliveau hosted the program for 10 years. It helped increase the popularity of a number of musicians, like Lionel Daunais and Claude Champagne, as well as Quebec authors Robert Choquette and Jovette Bernier.

In 1939, Guy Mauffette produced Grandes émissions du théâtre contemporain on CBF, the relatively new CBC station in Montreal. Other programs in the same genre were introduced on CBF. At the beginning, these programs aired mostly classical repertoire, but gradually expanded to include works from Quebec, notably in programs like Entrée des artistes, Radio théâtre Ford and L’équipe aux quatre vents. By the end of the Second World War, radio theatre from Quebec writers Pierre Dagenais and Félix Leclerc, alongside Shakespeare, Racine, Chekhov or Corneille, was being broadcast(1).

The Radio Collège program was broadcast on CBC from 1941 to 1956, during which it varied from four to eight hours a week. Over the years, a number of courses and lectures covering various academic fields were presented, as well as courses on French and international theatre, and music courses covering anything from music theory to Mozart and opera(2).

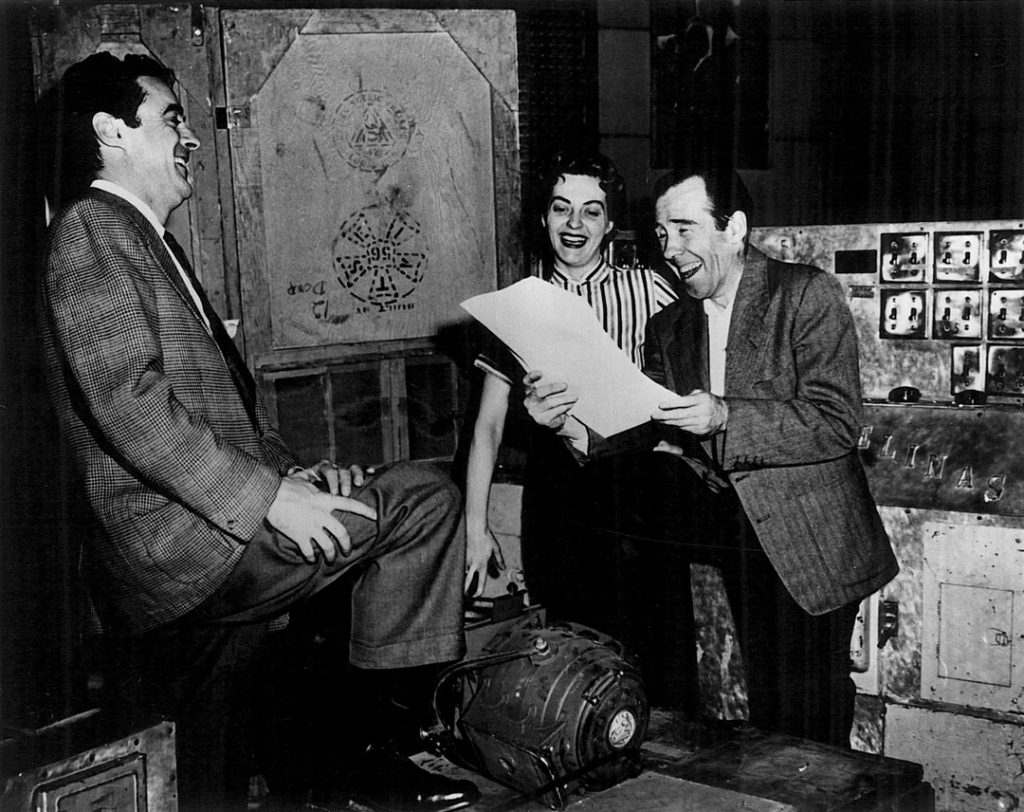

During the 1950s, the show Nouveautés dramatiques, directed by Guy Beaulne and broadcast on CBF, was intended as a dramatic writing workshop for radio. Several writers participated, including Yves Thériault, Yvette Naubert, Félix Leclerc, Marcel Dubé, Louis- Georges Carrier, Louis-Martin Tard and Claude Jasmin.

Then, Billet de faveur, Flagrant délit, Le théâtre de Québec, Le théâtre de poche, and Studio d’essai followed on CBF. This helped new writers, like Hubert Aquin and Jacques Languirand, gain popularity throughout the 1960s. Similarly, young actors, like Robert Gadouas, sat behind the microphone.

Throughout the 1970s, the CBC continued to broadcast radio theatre, notably during the program Premières between 1970 and 1986, and La Feuillaison, where works by Jacques Godbout, Pierre Turgeon, Normand Chaurette, Arlette Cousture and many others were introduced.

––––––––––––––––

1. Renée Legris, Histoire des genres dramatiques à la radio québécoise, Montréal, Septentrion, 2011, p. 131

2. Pierre Pagé « Le théâtre de répertoire international à Radio-Collège (1941-1956) », L’Annuaire théâtral, no 12 (automne 1992), p. 53-87; retrieved from [https://doi.org/10.7202/041175a].

Being a successful new form mass media, it is not surprising that in its first years, radio adapted the printed serial novel into the radio drama(1).

In Quebec, starting in 1935, the first francophone heroes could be followed daily in a radio drama. Robert Choquette, poet, novelist and screenwriter, wrote the French-language radio show Le curé du village(2). It was on the air every evening for 15 minutes between January 1935 and June 1938 on station CKAC(3). The first season was a great success and it had good ratings in the second season. The show became a real social phenomenon, with city dwellers and rural residents gathering together with neighbours to listen(4).

This literary genre would experience phenomenal success in Quebec. Americans called it "soap opera" because programs were generally sponsored by manufacturers of household or personal hygiene products.

Robert Choquette wrote other radio dramas like La Pension Velder and Métropole. Soon, works from Claude-Henri Grignon (Un homme et son péché), Henry Deyglun (Vie de famille), Jean Desprez, known by his pen name of Laurette Larocque (Jeunesse Dorée, Yvan l’intrépide), Louis Morrisset (Grande sœur, Vers le soleil avec tante Lucie, Rue des pignons, Face à la vie), Roger Lemelin (La famille Plouffe), Geneviève Guèvremont (Le survenant) and Françoise Loranger (La vie commence demain) to name just a few, played on the radio.

The genre also gave many actors the opportunity to make themselves known to a larger audience. Le curé du village featured performers, including Denise Pelletier, Juliette Béliveau, Marjolaine Hébert, Paul Guèvremont, Ovila Légaré, Roland Chenail, Yvette Brind’Amour and Guy Mauffette, who would become well-known to the general public.

––––––––––––––––

1. Soap operas were common in 19th-century newspapers, where readers could follow the adventures of their favourite heroes every day. Competition between daily newspapers was fierce, and this form of mass culture was selling copies. Some of the serials were by beginners, but great authors such as Zola, Balzac and Maupassant also contributed to this popular literary genre.

2. Pagé, op.cit., p. 377.

3. Retrieved from [https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Cur%C3%A9_de_village_(radio)]

4. Idem.

Quebecers love comedy shows today and this has been true for a long time! Humorous sketches first appeared on French-language radio at the beginning of the 1930s and they were the forerunners to the trendy radio dramas that began to be broadcast at the end of the decade.

"Robert Choquette and Alfred Rousseau were the first comedy writers. Humorous programs Au coin du feu (1931-1932) and Le Vieux Raconteur (1932-1933) focused on painting a picture of the social environment of the rural and regional world. L’Auberge de la forêt noire aired between October and December 1933, and in 1935 on CHLP, and L’Auberge des chercheurs d’or by Alfred Rousseau, aired on CKAC and CKCH between October 1934 and March 1935, presented a series of sketches in a narrative continuity with recurring characters. A humorous series by Alfred Rousseau, Les Aventures de quatre domestiques, was broadcast on CHLP between September and December 1936(1)."

Besides the authors mentioned above, people like Gratien Gélinas, Ovila Légaré, Henri Deyglun, Claude Robillard and Édouard Baudry wrote a lot of radio comedy. Sketches made for the radio were sometimes satirical. Throughout the 1940s, Émile Coderre created the character Jean Narrache in his series Rêveries de Jean Narrache, which was broadcast across several Quebec stations. The writings of Jovette Bernier led to the series of humorous sketches Quelles nouvelles between 1939 and 1956.

"Without a doubt, it was the program Chez Miville (1956-1970), created by Paul Legendre, that we find the greatest diversity of comedy styles. Each writer – Albert Brie, Louis-Martin Tard, Michel Dudragne, Jean Stéphane, Louis Pelland, Louis Landry – had developed a concept of comedy that expressed their vision of the world(2)."

The importance of Les joyeux troubadours, a CBF program that aired daily from 1941 to 1977, cannot be overlooked. The show resembled a variety program with humorous scripts and jokes.

the serial “Jean Narrache”, 1944. Source: Renée Legris, Histoire des genres dramatiques à la radio québécoise, Septentrion, 2011.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, comedy shows appealed to actors who saw radio as an essential stepping stone for their careers. Just think of how famous Tex Lecor and his associates (Roger Joubert, Louis-Paul Allard, Pierre Labelle) became as part of the Nouveau festival de l’humour québécois (New Festival of Quebec humour) that was broadcast weekly between 1974 and 1989 at CKAC, and Rock et Belles Oreilles (Guy A. Lepage, Richard Z. Sirois, Chantal Francke, Bruno Landry, Yves P. Pelletier and André Ducharme), which debuted on CIBL-FM community radio in 1981.

––––––––––––––––

1. Legris, op. cit., p. 58.

2. Pagé, cited on Legris, op. cit., p. 66.

Accessing radio reception of American stations was relatively easy in Canada. The American stations had powerful financial and technological resources while those of Canadian stations were limited. Therefore, for Canadian English-language stations, since language was not an obstacle, they regularly bought programming from American stations instead of producing their own.

In order to counter this invasion, Canadian networks were formed first around Canadian National Railway Company (CN) radio stations. This network was replaced in 1932 with the arrival of the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission (CRBC), which itself was replaced in 1936 by the English-language network of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC).

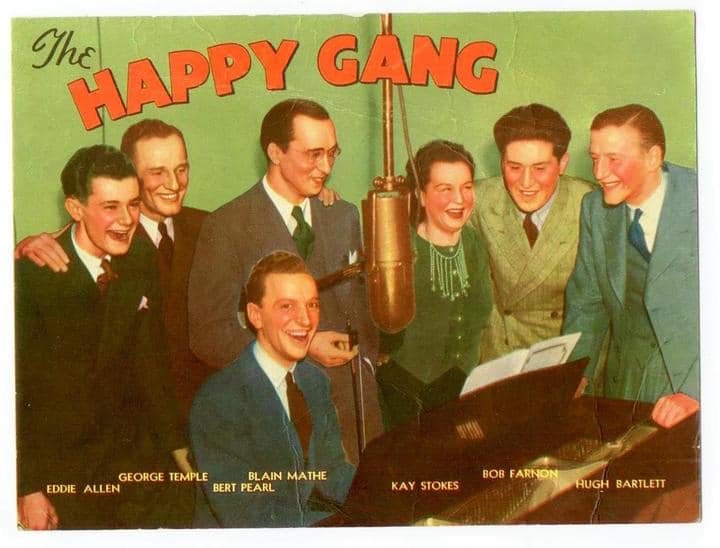

This new network allowed for the creation of Canada-wide programs, such as the variety show The Happy Gang, the family radio show The Craigs and, of course, Hockey Night in Canada. However, it was during the Second World War that CBC programs became very popular.

Several war-related soap operas emerged: Theatre of Freedom, Fighting for Navy, and Soldier’s Wife are a few examples. Theatre pieces by different Canadian English-language writers, like Andrew Allan, Esse Ljungh, Rupert Caplan and J. Frank Willis were also broadcast. Even comedy shows were popular during the war with duo Wayne and Shuster debuting in 1941(1).

––––––––––––––––

1. Retrieved from [https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/publications/archivist-magazine/015002-2131-e.html]

The strength of the radio drama certainly depended on the quality of writing and on its performers, but it also depended on the added sound effects. As Robert Choquette said, "The theatre on the radio is a theatre for the blind(1)."

"Suddenly, the sounds of the street were heard, the rumours escaping from a snack bar or a restaurant, the atmosphere of a country household, or the family brouhaha at mealtime; in these recreated universes, the listener rocked like in a dream and his imagination activated a thousand pictures(2)."

Sound effects creators are an artist on their own right. Some, like Marcel Giguère, whose beginnings on radio date back to 1939, became known to the general public by also making a career as an actor.

"The name Marcel Giguère is now ranked among the most useful craftsmen on the radio. In addition to his noisemaking qualities, (a profession that he possesses) Marcel Giguère possessed innate comic gifts. He has a very big imagination and has so much talent to spare that he can afford to give valuable advice to directors(3)."

––––––––––––––––

1. Du Berger et al., op. cit., p. 228.

2. Idem, p. 232.

3. Radiomonde, 27 juillet 1946, p. 8.

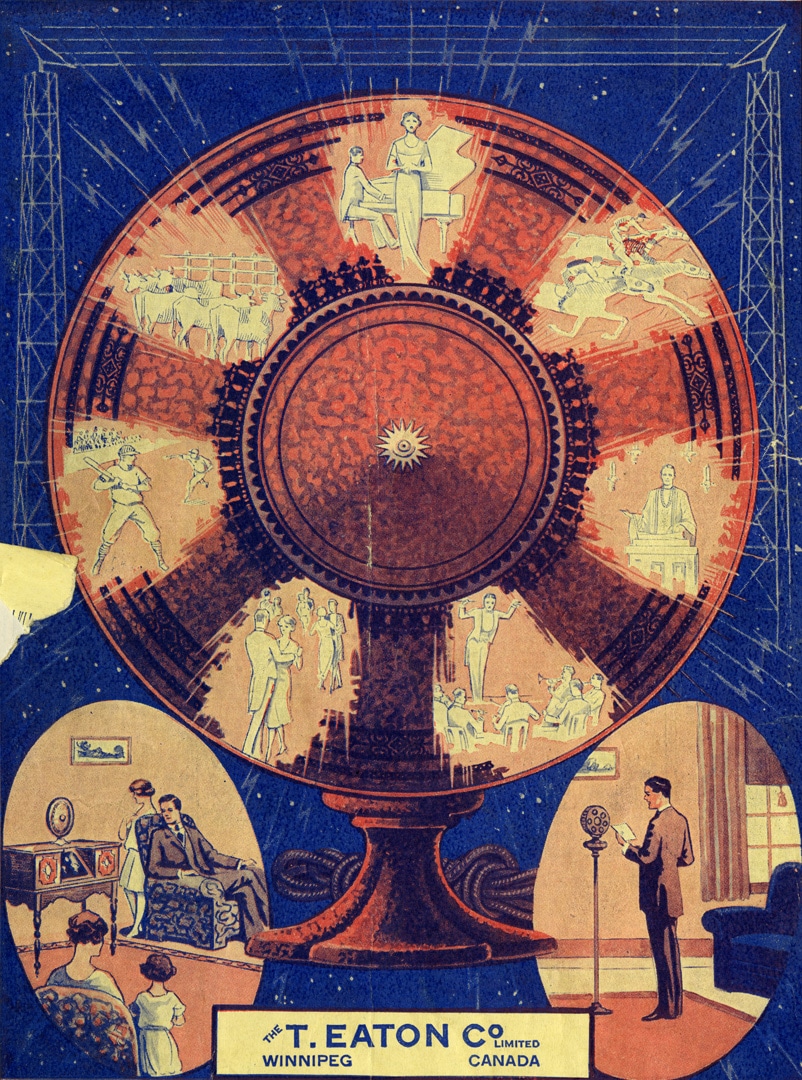

Eaton's catalogue 1926-1927 By 1926, the T. Eaton Company had understood the various forms of entertainment that radio could bring to the home. They are drawn here on the membrane of a cone speaker.